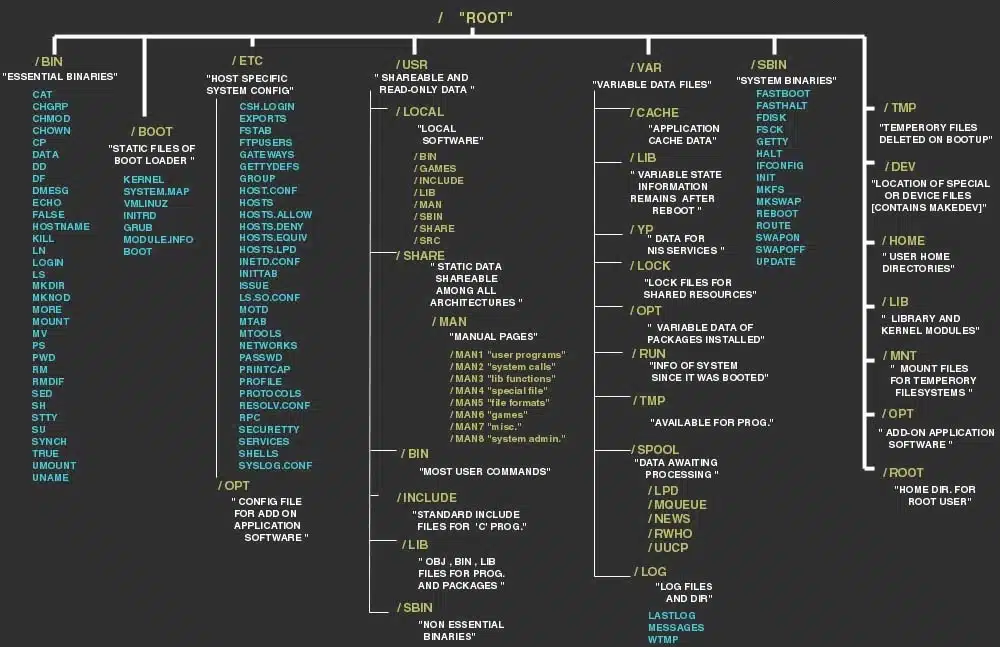

In order to manage all those files in an orderly fashion, man likes to think of them in an ordered tree-like structure on the hard disk, as we know from MS-DOS (Disk Operating System) for instance. The large branches contain more branches, and the branches at the end contain the tree’s leaves or normal files. For now we will use this image of the tree, but we will find out later why this is not a fully accurate image.

/Primary hierarchy root and root directory of the entire file system hierarchy.

/binEssential command binaries that need to be available in single user mode; for all users, e.g., cat, ls, cp.

/bootBoot loader files, e.g., kernels, initrd.

/devEssential devices, e.g., /dev/null.

/etcHost-specific system-wide configuration filesThere has been controversy over the meaning of the name itself. In early versions of the UNIX Implementation Document from Bell labs, /etc is referred to as the etcetera directory, as this directory historically held everything that did not belong elsewhere (however, the FHS restricts /etc to static configuration files and may not contain binaries). Since the publication of early documentation, the directory name has been re-designated in various ways. Recent interpretations include backronyms such as “Editable Text Configuration” or “Extended Tool Chest”.

/etc/optConfiguration files for add-on packages that are stored in /opt/.

/etc/sgmlConfiguration files, such as catalogs, for software that processes SGML.

/etc/X11Configuration files for the X Window System, version 11.

/etc/xmlConfiguration files, such as catalogs, for software that processes XML.

/homeUsers’ home directories, containing saved files, personal settings, etc.

/libLibraries essential for the binaries in /bin/ and /sbin/.

/lib<qual>Alternate format essential libraries. Such directories are optional, but if they exist, they have some requirements.

/mediaMount points for removable media such as CD-ROMs (appeared in FHS-2.3).

/mntTemporarily mounted filesystems.

/optOptional application software packages.

/procVirtual filesystem providing process and kernel information as files. In Linux, corresponds to a procfs mount.

/rootHome directory for the root user.

/sbinEssential system binaries, e.g., init, ip, mount.

/srvSite-specific data which are served by the system.

/tmpTemporary files (see also /var/tmp). Often not preserved between system reboots.

/usrSecondary hierarchy for read-only user data; contains the majority of (multi-)user utilities and applications.

/usr/binNon-essential command binaries (not needed in single user mode); for all users.

/usr/includeStandard include files.

/usr/libLibraries for the binaries in /usr/bin/ and /usr/sbin/.

/usr/lib<qual>Alternate format libraries (optional).

/usr/localTertiary hierarchy for local data, specific to this host. Typically has further subdirectories, e.g.,

/usr/local/bin/ ,

/usr/local/lib/,

/usr/local/share/.

/usr/sbinNon-essential system binaries, e.g., daemons for various network-services.

/usr/shareArchitecture-independent (shared) data.

/usr/srcSource code, e.g., the kernel source code with its header files.

/usr/X11R6X Window System, Version 11, Release 6.

/varVariable files—files whose content is expected to continually change during normal operation of the system—such as logs, spool files, and temporary e-mail files.

/var/cacheApplication cache data. Such data are locally generated as a result of time-consuming I/O or calculation. The application must be able to regenerate or restore the data. The cached files can be deleted without loss of data.

/var/libState information. Persistent data modified by programs as they run, e.g., databases, packaging system metadata, etc.

/var/lockLock files. Files keeping track of resources currently in use.

/var/logLog files. Various logs.

/var/mailUsers’ mailboxes.

/var/optVariable data from add-on packages that are stored in

/opt/.

/var/runInformation about the running system since last boot, e.g., currently logged-in users and running daemons.

/var/spoolSpool for tasks waiting to be processed, e.g., print queues and outgoing mail queue.

/var/spool/mailDeprecated location for users’ mailboxes.

/var/tmpTemporary files to be preserved between reboots.

Types of files in Linux

Most files are just files, called regular files; they contain normal data, for example text files, executable files or programs, input for or output from a program and so on.

While it is reasonably safe to suppose that everything you encounter on a Linux system is a file, there are some exceptions.

Directories: files that are lists of other files.

Special files: the mechanism used for input and output. Most special files are in /dev, we will discuss them later.

Links: a system to make a file or directory visible in multiple parts of the system’s file tree. We will talk about links in detail.

(Domain) sockets: a special file type, similar to TCP/IP sockets, providing inter-process networking protected by the file system’s access control.

Named pipes: act more or less like sockets and form a way for processes to communicate with each other, without using network socket semantics.

File system in reality

For most users and for most common system administration tasks, it is enough to accept that files and directories are ordered in a tree-like structure. The computer, however, doesn’t understand a thing about trees or tree-structures.

Every partition has its own file system. By imagining all those file systems together, we can form an idea of the tree-structure of the entire system, but it is not as simple as that. In a file system, a file is represented by an inode, a kind of serial number containing information about the actual data that makes up the file: to whom this file belongs, and where is it located on the hard disk.

Every partition has its own set of inodes; throughout a system with multiple partitions, files with the same inode number can exist.

Each inode describes a data structure on the hard disk, storing the properties of a file, including the physical location of the file data. When a hard disk is initialized to accept data storage, usually during the initial system installation process or when adding extra disks to an existing system, a fixed number of inodes per partition is created. This number will be the maximum amount of files, of all types (including directories, special files, links etc.) that can exist at the same time on the partition. We typically count on having 1 inode per 2 to 8 kilobytes of storage.

At the time a new file is created, it gets a free inode. In that inode is the following information:

Owner and group owner of the file.

File type (regular, directory, …)

Permissions on the file

Date and time of creation, last read and change.

Date and time this information has been changed in the inode.

Number of links to this file (see later in this chapter).

File size

An address defining the actual location of the file data.

The only information not included in an inode, is the file name and directory. These are stored in the special directory files. By comparing file names and inode numbers, the system can make up a tree-structure that the user understands. Users can display inode numbers using the

-i option to

ls. The inodes have their own separate space on the disk.

Fuente